|

|

|||

|

Inventing Kindergarten - Introduction

|

THE

SEED-BED: |

|||

|

||||

| Stick Laying. Chromolithograph from Froebel's Kindergarten Occupation for the Family, a kindergarten teaching set for home use. E. Steiger & Company, New York, 1977 | ||||

| Jessie Georgina Varker is not a name usually listed among the canon of modernist art masters. Yet in Ms Varker’s work from the 1880’s we witness the essential elements of the modernist style. Petite, collaged masterpieces that call to mind early works of the Op-Art movement, the pieces consist of brilliantly colored paper squares cut and folded into gem-like assemblages and pasted into the pages of a concertina album. A series of these albums, each a miniature cosmos of handcrafted female labor, form the backbone of this exhibition. Some encompass more than a hundred pages and extend to more than seventy feet of shelf space. These dazzling exercises in geometric harmony are executed in humble domestic mediums including colored thread sewn onto cards and patterns pricked out with pins on sheets of white paper. None of these pieces, however, were created as works of “art” – they were teaching tools, made to inspire young children in the original kindergarten system of education. | ||||

|

||||

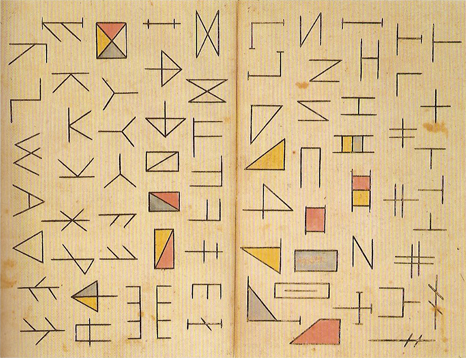

| The first two pages from Zum Nachzeichnen für Kinder (Copy Drawing for Children) by B.Adamek. Vienna, c. 1830 | ||||

| Like

thousands of women around the world during the latter half of the

nineteenth century, Jessie Varker had been drawn into the kindergarten

classroom by the vision of the movement’s founder, Friedrich

Froebel. Most of us today experienced kindergarten as a loose assortment

of playful activities - a kind of preparatory ground for school proper

- but in its original incarnation kindergarten was a highly formalized

system that drew its inspiration from the science of crystallography.

Properly conducted, Froebel believed that education for the very young

would enable the flowering of human potential, for kindergarten was

literally the garden of children where growing buds might unfurl and

bloom. “By education,” he declared, “the divine

essence of man should be unfolded, brought out, lifted into consciousness.”

For Froebel, the education of children was nothing less than a holy

duty, “a necessary, universal requirement” that was beginning

to assert itself as the birthright of all humanity. Under Froebel’s insight, the teaching of infants was given a theoretical framework that would expand the minds not just of children, but also of their teachers. Women like Jessie Varker who flocked to teach this system grasped the opportunity to contribute to what they hoped would be substantial societal improvements for children and themselves. Denied access to universities and other places of higher learning, women of intellect were also yearning for mental stimulation and Froebel’s system would provide an outlet of expression for hundreds of thousands of women the world over. From the oeuvre of early kindergarten, it is largely the teachers’ output that has been preserved and in this remarkable body of work we witness the stirrings of a new era. As this exhibition suggests, in the work undertaken by kindergartners of the late nineteenth century we may locate the seed-bed of Modernist Art |

||||

|

||||

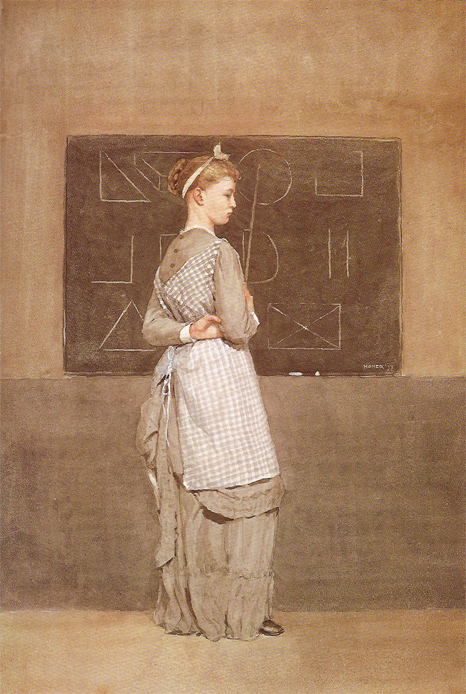

| Winslow Homer. Blackboard, 1877. Watercolor, 19 1/2 x12 1/8". Gift (partial and promised) of Jo Ann and Julian Ganz, Jr. in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. | ||||

| Not

until the late eighteenth century were young children viewed as fitting

subjects for systematic pedagogical reflection. Some scholars have

argued that the very idea of “childhood” is an invention

of post-Enlightenment Europe. In any case, following the Swiss innovator

Johann Pestalozzi, Froebel took upon himself the task of developing

a program by which young minds could be guided and formed. In his

opus The Education of Man, Froebel laid out his conceptual mission:

“The knowledge of life in its totality, constitutes a science,”

he wrote, “the science of life. Referred by the self-conscious,

thinking, intelligent being to representation and practice through

and in himself, this becomes the science of education.” In the remarkable book Inventing Kindergarten, scholar and collector Norman Brosterman traces the development of this revolutionary system from its founding in Germany in the 1830’s through its dissemination to the rest of the world. As Brosterman writes, the ultimate aim of the kindergarten movement “was to instill in children an understanding of what an earlier generation would have called ‘the music of the spheres’ – the mathematically generated logic underlying the ebb and flow of creation.” Philosophically, kindergarten was grounded in Froebel’s belief in the Unity of all things and in the existence of simple laws and principles underlying nature’s apparent complexity. As Froebel saw it, the crystal was the archetypal form from which we could derive a model for all of nature. The child herself could be seen as a crystal. Drawing on his years as a curator at the Mineralogical Museum at the University of Berlin, Froebel wrote that the role of education was to guide the development of the nascent, crystalline mind from “one-sidedness, individuality and incompleteness” toward “all-sidedness, harmony and completeness.” |

||||

|

||||

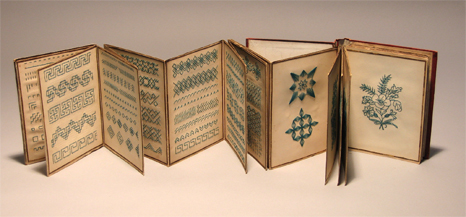

| Intricately detailed sewing workbook by Auguste Cohn. Germany, dated 1880. | ||||

| Froebel

designed his educational experience around a series of physical and

mental activities, among them singing, dancing and gardening. At the

heart of this pedagogical universe were formalized exercises centered

round a set of “occupational gifts,” what we today (with

sadly diminished vision) might call educational toys. Twenty in number,

the gifts were tools designed to encourage the exploration of form.

How, for example, could lines or squares or cubes be arranged to produce

the form of a bird or a chair or a tree, or a pleasing, snowflake

symmetry. As a crystal grows from its molecular seed, so too animals,

plants and buildings could be assembled from the primitive units of

the Froebelian gifts. Cutting and folding paper, weaving together

wooden sticks, sewing thread onto cards, and building with blocks

of various sizes, teachers and pupils together would construct the

world. The exercises focused on making three types of forms: forms

of nature (or life, and things of the world), forms of beauty (art),

and forms of knowledge (science, mathematics and especially geometry).

In the course of their training, teachers fabricated sample exercises

of “fancy work” that they arranged in albums, progressing

from simple to more complex designs. After Froebel’s death in 1852 kindergarten quickly spread throughout Europe and to its nation’s colonies, including America, where Susan Blow opened the first public kindergarten in St Louis in 1873. By the 1880’s Japan boasted dozens of kindergartens and the system was entrenched in Russia well before the Revolution. As with Socialism, kindergarten’s proponents saw it as a potential way to achieve “a better more equitable world for the working class.” But nowhere were the effects of kindergarten more widely felt than on the aesthetic front. Brosterman argues that children of the classic kindergarten era were in effect “programmed” to see the world in a new way. On the gridded surfaces of the special tables where they stacked blocks and pin-pricked patterns, these youngsters learned how to deconstruct and reconstruct representational space. Fertilized by the humus of kindergarten, the western aesthetic sensibility was reconfigured and Brosterman proposes that the visual revolution of the next century can be seen as an evolutionary outgrowth of this educational experiment. |

||||

|

||||

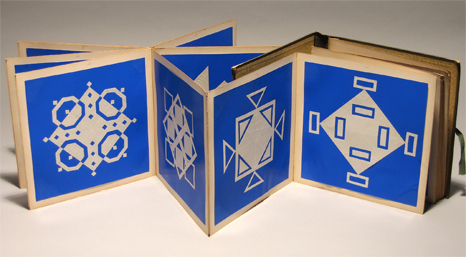

| Paper cutting album of Ina Getz. U.S., dated 1889. | ||||

Of

the forces that supposedly brought modern art into being, a wide

range of factors have been cited - industrialization, the “machine

age,” and psychosexual emancipation. Though kindergarten has

never been “fodder for argument over absinthe and Gauloises

in Montmartre cafes,” Bosterman suggests that its influence

on modern art “has been largely ignored because its participants

were in the primary band of the scholastic spectrum.” To which

we may add that the gender of its practitioners was overwhelmingly

female. In the standard narratives of art-historical criticism,

women are not only absent from the canon of modern masters, but

female activities, interests and occupations have been cast as mostly

irrelevant to the movement itself. This exhibition challenges that

view, locating women and children at the origin of this aesthetic

upheaval. |

||||

|

||||

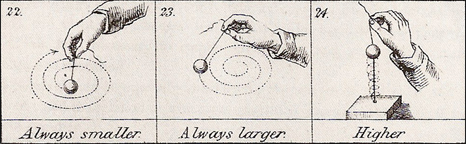

| Suggested exercises with the first gift. From plate 1b. Practical Guide to the English Kindergarten by Johann and Berthan Ronge, London, 1855 | ||||

| © 2003–2018 The Institute For Figuring | ||||